EVEN WHEN YOU DON’T KNOW HOW TO DRAW

*This page contains affiliate links

I’m going to assume you want to write a graphic novel, but aren’t quite sure where to begin. If you’re still on the fence because you are a writer and not an artist, I recommend you read this post first.

As a writer, I have a strong foundation in storytelling with words. Visual storytelling operates under the same principles with additional elements. It’s more than just illustrations in place of descriptions. Composition, color, lettering, etc. These all play a part in how the reader absorbs the story.

Below, I’ve listed the key visual elements the writer needs to know so they can write a successful script. There are more illustration rules, and while I believe writers should get to know all of them, these are the top-priority for writers.

Storytelling & Page Architecture

1. Page turns

The final panel on the right-side page is the “page-turn”. This is where readers will naturally stop. As a writer, it is your job to incentivize the reader to turn the page and keep reading. So, when you write the script, it helps to keep track of the left and right pages and make sure that the final panel on the right leaves a question unanswered, the same way you would write a chapter end.

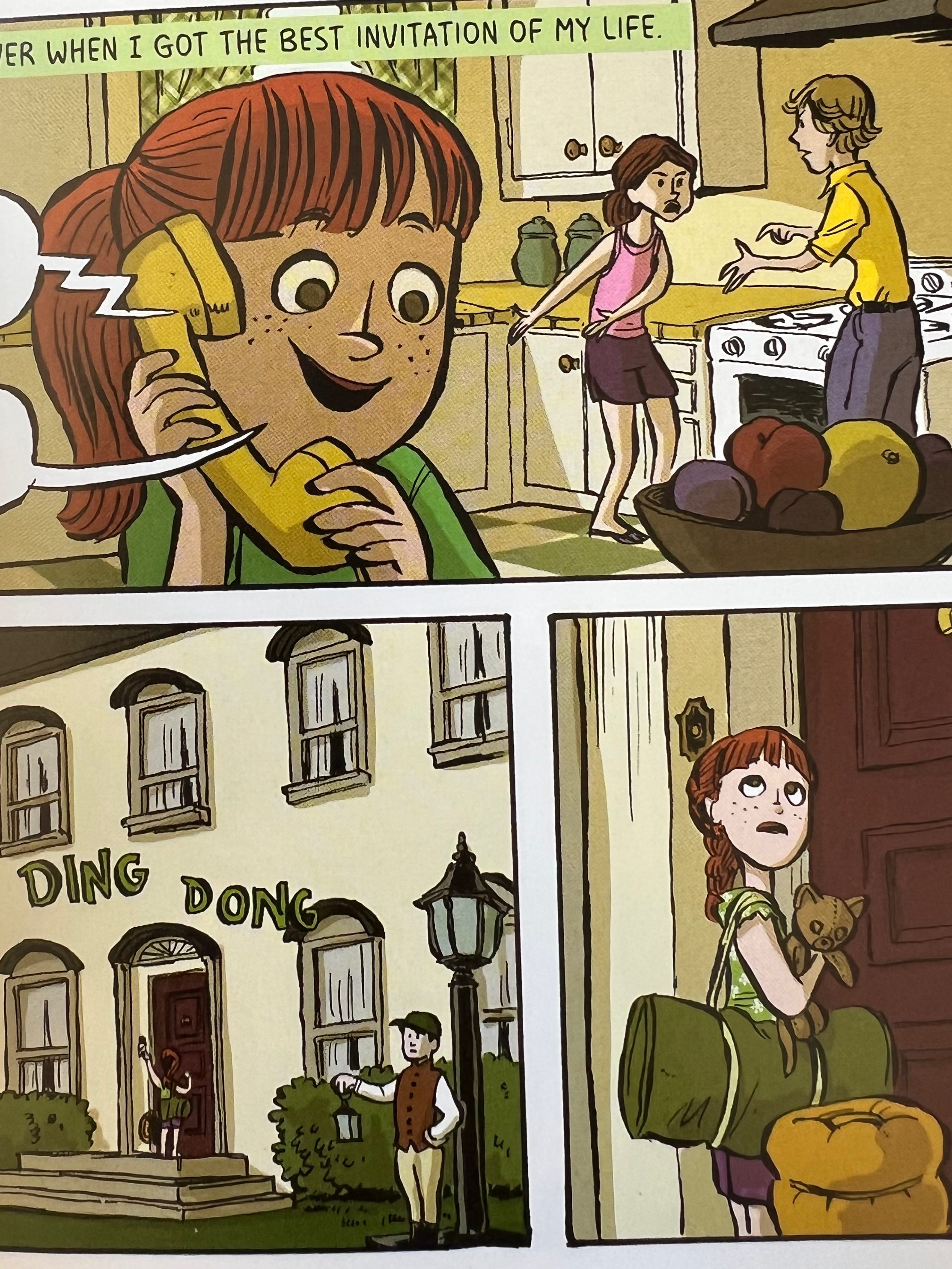

These questions don’t have to be huge, plot-changing questions. They can be quiet, visual cues, like a character opening a door or an unfinished conversation. Check out the page turn in the example below from Real Friends by Shannon Hale and LeUyen Pham.

In the final panel, the main character, young Shannon, is clearly intimidated by the size of her friend’s house. As a reader, we know the door is about to open and feel uncertain with her. What kind of family is inside? Will they be as stiff as the house and lawn suggest?

These aren’t life or death questions, but we have to know what comes next.

In the script, you might write the description and the character’s emotion in the final panel of the page as simply: “Shannon looks up at the enormity of the house with trepidation.” The illustrator will then translate the emotion into a visual beat.

2. Number of panels per page

Every page needs one dominant beat. That could be the largest panel, the most detailed moment, or the emotional payoff.

After you determine what that beat is, and the scene pacing, you can decide how many other panels you need to support it. Most pages will have 4-6 panels, a few will have more and a few less. I’ve seen as a many as 9 panels, and as few as 1, known as a splash page. These pages serve very specific roles, which we’ll cover next.

For the most part, stick to 4-6 panels.

3. Splash pages and double spreads

Splash pages–a single image covering the entire page–and double spreads–a single image that spreads across two pages from left to right–are reserved for reveals, transitions, or emotional climaxes.

In the script, you indicate these at the top of the page. “PAGE 1 (R) – 1 panel” for a splash page, and “PAGE 12 and 13 (L&R) – 1 panel” for a double spread.

4. Panels for pacing

The size and number of panels will directly effect story pacing. As a general rule of thumb, large panels move the story along faster, while smaller panels slow it down, and this is especially true for pages with a few large panels, and pages with more panels that are smaller.

Panel shape can also contribute to the pacing and to emotional impact. Slanted lines suggest movement, and slanted panel borders indicate urgency. Panels without borders lets the scene unfold without breaks.

Regular grids (like 6 or 9 panels) create a steady, deliberate rhythm. Readers slow down almost automatically. This works well for conversations, contemplation, internal conflict, tension before action.

You can write panel shapes into the script if needed like this: “Panel 3: [slanted to the right]”

5. Every panel must…

Panels are units of time and attention. If a moment doesn’t change information, emotion, or time, it probably doesn’t need a panel.

Dialog, Lettering, and Readability

1. Word count per panel

In novels, a page’s entire real estate is filled with words or nothing. Obviously, graphic novels are entirely illustrated. Words must be kept to a minimum. Here are some general guidelines:

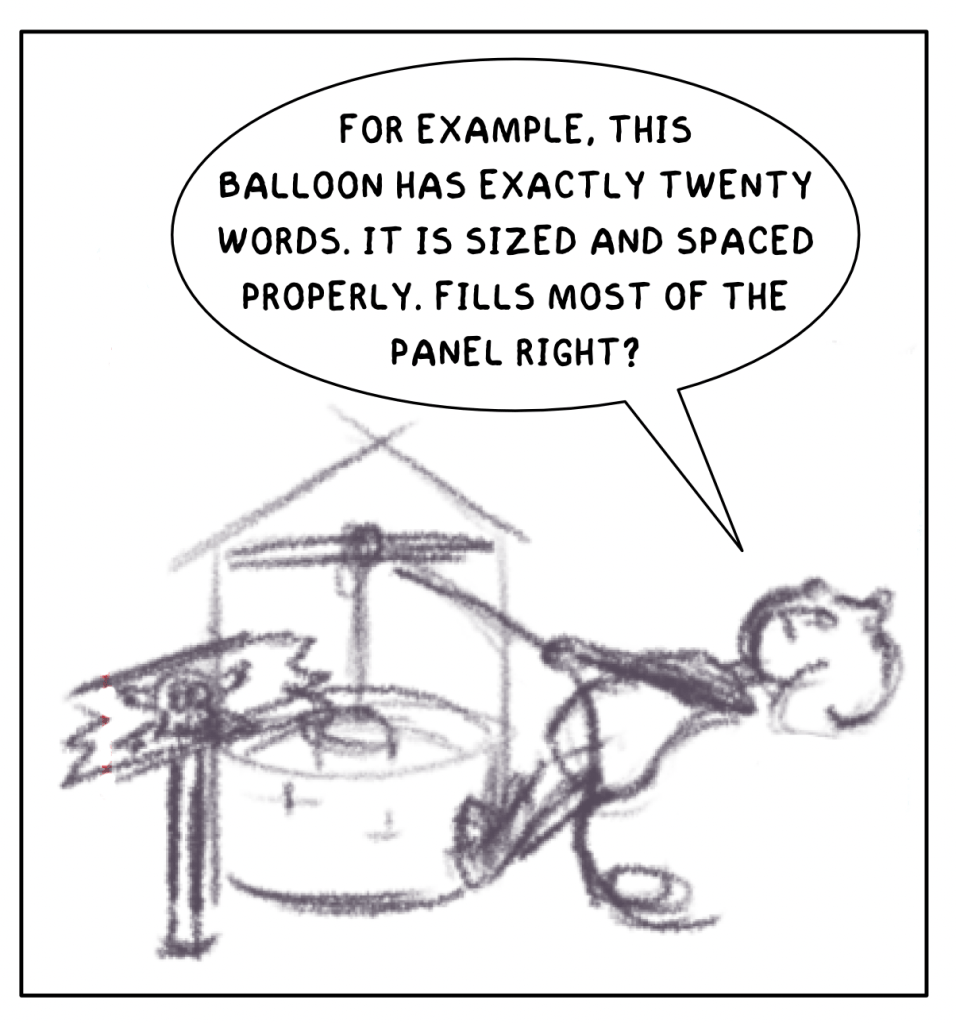

Aim for 15–25 words per panel total.

That includes:

- speech balloons

- captions

- any other text in the panel

If a balloon looks like a paragraph, it will kill pacing.

In the above sample, the balloon fills a large portion of the panel. Any more words, and it would intrude on the illustration. This panel is average sized, so a bigger panel could accommodate more words, but you still don’t want to go too far because then the balance of the panel is off and readers will get fatigued. (I know it sounds silly when we’re talking fewer than fifty words.)

2. Silent panels and wordless sequences

Not all panels need text. Write silence into the script. Allow the illustrator to convey emotion purely through art.

3. Caption vs dialog responsibility

In graphic novels and comics, captions refer to narration and labels, not the information that goes under an image. Captions support the story. They can be written into the script by writing “caption” in place of a character’s name in the dialog section.

And Finally… TRUST THE ARTIST

Write the script to your satisfaction, but leave room for the artist to take creative liberty. Some artists like to have detailed instruction, but when you collaborate on a project, the artist becomes a co-author. They will have ideas to strengthen your project. And if you’ve done your job finding someone compatible with you, then you will likely be awed by your illustrator’s choices.

Did you already know all these illustration rules? What was new to you? Share your thoughts in the comments below or in my Substack community space.

Next week’s post will go over freewriting–a powerful skill for any writer.

Not sure whether you want to try your hand at graphic novels? Read this post.

Want to read more original work? Check out my Medium account for flash fiction, personal essays, and articles.

Be sure to subscribe to my newsletter: WITH LOVE, FROM THE FUTURE for more personal letters and updates.

You can find my book recommendations in my Bookshop, Amerixicana Books.

And if you are looking for classic literature for class, or for your home collection, check out my publishing imprint, Simply Classic Books.

Leave a comment